Ordinary Human Poverty

Sharon September 24th, 2008

At one point in his writings, Sigmund Freud (who, btw, was not at all the caricature that many readers imagine him as and who is well worth reading in his own right) wrote about the difference between two states - one of them abnormal, and subject to resolution by the “talking cure,” the other ordinary and not necessarily remediable. The first he called “neurotic misery,” the other “ordinary human unhappiness.” His point was that psychoanalysis could only address pathological states, neither it nor any other solution could preserve us from the ordinary bad experiences of being human, and that distinguishing between them was essential. Ordinary human unhappiness did mean, of course, that one was unhappy every second, merely that one accepted that normal human states had periods of suffering, sadness, anger and fear in them too - it was important to recognize that nothing, no tool, could ever make life good every second.

Riffing on Freud, for some years, I have been arguing that the reality of peak energy, climate change and our precarious financial situation was leading us towards re-experiencing “ordinary human poverty” - a state that I would argue is fairly normal, if at times unpleasant. I also believe it is the future for most of us. And it would be easy to imagine that this meant that our future was one of true horror, an pathological nightmare from which we cannot awaken. The despair many of us feel when we see that word “poverty” can’t be underestimated.

I think we are now at the point where the argument I’ve been making all these years - that peak oil will be less about whether there is gas in the gas stations or whether the grid crashes - and more about whether we can buy gas or whether the utility company shuts us off for nonpayment is pretty much certain. Right now, we are watching the crisis unfold mostly far from us. It is coming home - and rapidly, and we are shifting to a lower eocnomic level. For example, as the New York Times reports, retail chains are in real danger - remember, 70% of our economy depends on consumer spending. Most of us will cut back, and many chains will go bankrupt for lack of funds and credit - and that cascade of bankruptcies will further echo, as more and more of us who still have jobs and money to spend see no point in buying things at successful chains - why bother when the same jeans are available at 75% off at the going out of business sale of another store in the same mall?

We could make much the same analysis for many other segments of the economy. Whence the high paying NYC and other urban restaurants that depend on high finance types buying expensive meals? Poof! Whence travel and tourism in an era of unemployment and expensive gas. We may go some places - those who still have money may head to the beach, rather than Cancun - but the overall amount of wealth flowing through the economy will drop like a stone. And the fear takes the rest of it with us, as we become afraid to spend, afraid to invest, afraid to lose what little we’ve got left. Bailout or no, the economy is headed into something deep and dark, and most of us are going into this new world with it. Poverty is about to go back to being our human norm - just as it always has been for most of the world’s people.

And yet, the reason I’m using Freud’s language here isn’t just to remind us that poverty is a normal state for human beings. It is in part to imply that there is a distinction between the deep suffering of what I would call “pathological poverty” and the functional poverty that is “ordinary human poverty”, sometimes unpleasant, probably always troubling in comparison to the relative wealth we’ve had, but basically livable state. In it one can have periods, even long periods of happiness and security and comfort along with some less pleasant momemtns. And I believe that while none of us can insulate ourselves entirely from the trauma of the darker ends of this, there is a great deal we can do to ensure that our coming poverty is not the pathological kind.

I find this reassuring then, when I read Dmitry Orlov’s latest account of where we stand in his “Five Stages of Collapse” - on the one hand, there’s not much cheery about the fact that we’re jumping over from Stage One to Two - and I think he’s right. But there is the reality that we can do a great deal to keep the elevator from dropping down to the basement.

What is the distinction between “pathological poverty” and “ordinary human poverty?” Well, cast back in your heads to your grandparents or great-grandparents. Among the stories of hardship in post-war Europe and Asia, of recurring crises across the Globe, and of the Great Depression in America are likely to be moments that distinguish between the pathological poor. “We were very poor, but there was always food on the table.” “We were poor, but we didn’t really know it.” “It was a struggle, but we were happy.” We will also hear stories the other side of poverty - the pain of hunger, the blind terror of being turned off with no place to go, the deaths and the pointless losses and tragedies.

The question becomes how do we turn this story into one where most of us can say “We were poor, but we had enough - just enough, but enough.” And where our kids may grow up not really realizing just how poor we were? How do we accustom ourselves to the ordinary human unhappiness (which, after all, isn’t unhappiness every moment, merely a recognition that most people aren’t happy all the time) that is our shift in wealth, without allowing ourselves to fall through the floor, into the deeper stages of collapse?

There are three answers to this. The first is to reduce your needs. I expect that for a long time, the stigma that attaches to any kind of poverty will keep many of us struggling to keep up appearances. We are likely to feel ashamed the first time we have to ask for help, ashamed that our clothes are no longer as fine, that dinner is plainer and that we now share our homes. The best way, I think to get over these feelings is to get over them in advance - to change your values as so many here have. Thrift shop clothes and patches should be sources of pride, symbols of your independence from industrial manufacturers. The food on the table - and the people who share it - are the point - not whether high-social value elements like wine and meat are present. The need to speak out against the culture that tells us that poor is dirty and bad becomes paramount - because the more resources we waste keeping up appearances the harder it will be to adapt.

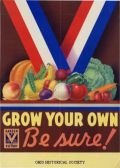

The second is self-sufficiency of the kind most of us are trying to achieve. The garden, the sewing needle, the saw and hammer, the ability to make and repair, to grow and produce and nurture things - these are things that demonstrate, as Jeremy Seabrook has contended, the opposite of poverty is not wealth, it is self-sufficiency. None of us will ever be wholly self-sufficient - but to be able to say that it doesn’t matter if you can afford shoes this year because you can repair last year’s boots, or to not have to spend much of your money on food means that you have a much better chance of covering that emergency medical bill or the property taxes.

But these things alone are not sufficient. One’s self-sufficiency can be taken away too easily when we lose access to land. You can lower your standards to allow “poor but decent” but when we get to “filthy and rat infested” that’s not such a good idea. The only way to live in the world of ordinary human poverty is to live there in a world where your pocket isn’t picked constantly, where you aren’t the victim of endless resource conflicts, where your government doesn’t sell your future out. And the only way to be a nation of reasonably self-sufficient, ordinarily poor people living decently is this - to remember that the reason we use the word “ordinary” here is that there are a lot more of us peasants than there are of the powerful. The truth is that repressive governments, of the sort we have had and are rapidly entrenching are scary - but they never have enough troops, enough power to stand up against the unified dignity of those who are simply ordinary, and simply want enough. But that requires that we trust each other, that we work together, that we create the institutions of ordinary poverty, the ones that have fallen into disuse - Granges, Unions, Consumers Unions, neighborhoods, voting blocs, and larger groups that can be used to pull us together. These things too are ordinary and human - and it is getting to be time to build them.

Sharon